A Dive into Ethereum Transaction Details

One of the beauties of a public blockchain is that anyone can see anything. In this post, I’m going to dig into a couple of transactions from October 2020.

Previously published on my old Blog 31st October 2020

Introduction

Previously I described how a market cap fund assets under vault (AUV) change by the issue and redemption of fund units (tokens). This is the primary market for the fund. There is also a secondary market where the fund tokens are traded for other assets. This is typically ETH, but could be any other asset available on the market.

This post is about trades on the primary and secondary markets, and how movements in the secondary markets drive the primary market to capture value from miss priced assets (i.e. arbitrage between the two markets). I’ll be looking at the DPI index fund as I’m most familiar with it and there have been interesting trades recently.

Secondary market

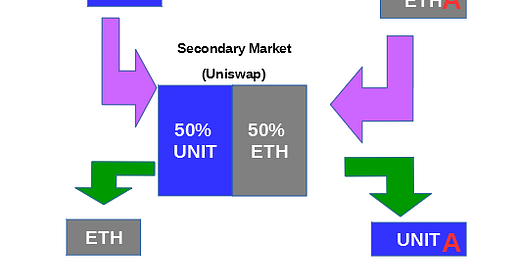

Figure 1 shows the basic operation of a typical market (e.g Uniswap). The pool contains equal values of both ETH and DPI. When someone makes a trade they add ETH (A) and remove DPI (Unit A). In order to maintain a constant total value for the two tokens, the pool increased the (internal) value of the DPI to compensate for the change in numbers of each.

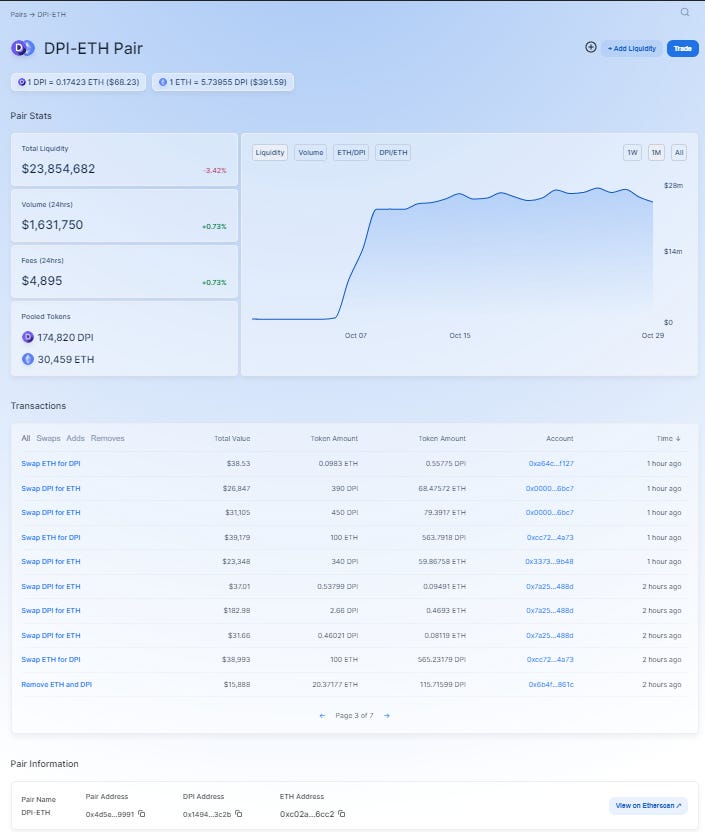

The largest secondary market for DPI is the Uniswap DPI-ETH pool (Figure 2). This currently has ~ $24 M liquidity, and it would take a trade of ~$500,000 to move the price by 2% (“Slippage”). [Previously $20 M].

At ~ 04:40 pm on the 31st October, a 100 ETH to DPI trade took place. This is a significant purchase and will have pushed the price in the pool slightly higher. This means that the token may have become worth more than the value of the tokens it represents.

Issuing more units to arbitrage the price

Unlike other tokens where the main opportunity to arbitrage is between different markets, one feature of funds like DPI is that more of the token can be issued (or redeemed) when as required. This arbitration is driven by the difference between the token price and the value of the underlying Net Asset Value (NAV). Figure 3 presents an overview of how such an operation can occur. Here a trader starts with ETH (ETH B) and takes the following steps:

They trade B ETH for the individual tokens on the market in the exact ratios to match the pool.

The individual tokens are placed in the pool issue unit (smart contract), and the DPI token minted.

The DPI tokens are deposited in the DPI:ETH pool trade for ETH (C ETH).

So long as C (minus gas) is greater than B, the trade has made a profit.

One block after the trade above, such an arbitrage trade was made. This was done using a flash loan and was completed in a single transaction. Table 1 presents a summary of the parts of the transaction and the value of each.

Overall the transaction make a profit of ~$140 which is ~0.45% based on the total values transferred. However, as the transaction was done in a single block using a flash loan, there no capital required to run the arbitration. Assuming that all the exchanges used a 0.3% pool fee, the trade will have paid $186 to the liquidity providers (with half going to the DPI-ETH pool).

Final thoughts

Such arbitration between markets is an essential part of an efficient market. Without such trades the secondary market will quickly drift from the underlying NAV. The economies of scale of large liquidity pools mean that arbitration becomes cost-effective for smaller deviations from the theoretical value of DPI.

Disclosure and Disclaimer

I’m a long term investor in crypto currencies including DeFi. I am an active member of the INDEXcoop which manages the $DPI fund.

This is not financial advice, all investments are risky, crypto investments are riskier than most. Do your own research. Do not invest more than you can afford to lose.